My First Adventure Bike Race: 3 Powerful Lessons from Sancho 200

It could be Ironman, ÖtillÖ, or a local 10k – just about every athlete has a “big” event on their radar. It’s just a matter of time when they get around to making it happen.

For me, the Sancho 200 was that event, and the 2020 Fall edition was the year.

The Sancho 200

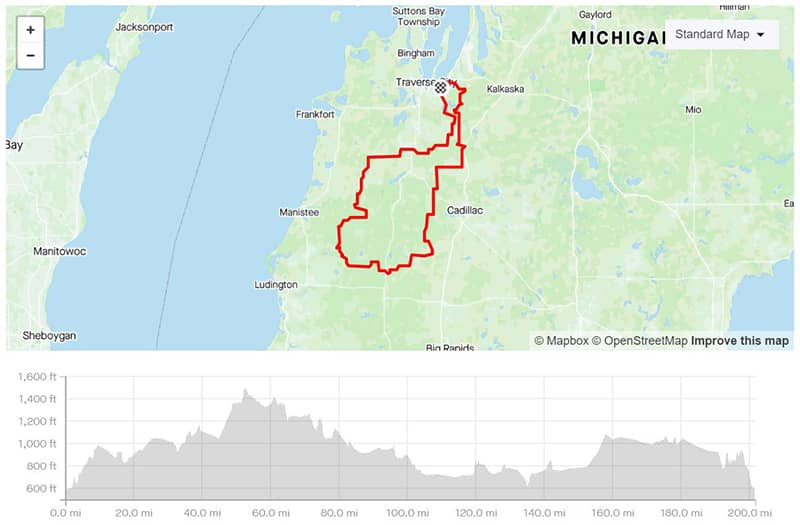

Sancho is an adventure bike race that goes down roads I grew up riding. It has a local sentiment, but it’s also my favorite type of bike racing – long, hilly, and scenic.

Sancho can be summarized as a mostly unpaved, 201-mile bike excursion that captures some of Michigan’s most scenic and remote backroads. A passionate friend of mine designed the route over countless rides and eventually made it a race in 2017.

During those early years, I would stop by the after-parties and leave awe-inspired watching the dusty riders come in. It was a different time, as the first years of Sancho were hot and fast, taking place in early June.

Adventure bike race – my first experience, but definitely not the last

Fast-forward to 2020’s race, which was pushed to mid-October due to the coronavirus, and the conditions were dramatically different – cold, wet, and slow. Just hours leading up to the race there was downpouring thunderstorms, leaving the course extra sloshy and sluggish.

Without going into every detail about the race, below I’ve distilled a few things that I learned during the experience. These are bite-sized mindfulness teachings that I hope to keep as reminders throughout my life as an adventure cyclist.

#1 – You went out too hard. Now what?

Contrary to my race strategy of starting easy and reserving my energy for the second half of the race, I chose to keep pace with the front pack. Perhaps it was the excitement of the race combined with my legs feeling especially good, but I knew in the back of my head it was a risky decision for my first adventure bike race of such distance.

The first quarter of the course is the most challenging, between the amount of climbing, loose sand, and technical sections. But this first part of the race was also my home turf.

I knew all the major sandy stretches, big mud puddles, and elevation gains where keeping momentum was crucial to avoid having to dismount and walk the bike. So I laid down a strong pace and ended up dropping the front pack where I had an experiential advantage.

There were a couple of sizable climbs early on, totaling about 1,200 feet (360 meters) within the first 30 miles. It wasn’t dramatically steep, but steady and seemingly never-ending.

At this point, it was only the second hour of the race, so it was still completely dark out. Even with a good headlamp, visibility was short. The woods were dense and the ground was still sopping wet from the downpours from that night.

Dialing it down

As I looked down at my heart rate monitor to see 170 bpm, I knew I was going out way too hard. I crossed my fingers hoping my initial burst of effort wouldn’t be a costly mistake hours down the road. And the thought of eating solid food seemed nearly impossible at that intensity.

So now what?

I reached mile 30 where the elevation flattened out for a few miles before eventually reaching some of the truly difficult climbs with even steeper grades. I dialed back my pace and consumed as much easy-to-digest sugar as I could. It was still early in the race and I had reluctantly drunk the one bottle Coke I brought with me. Certainly not the healthiest fueling plan, but one I felt necessary at the time.

Read also: Peak Performance Mindset – 21 Secrets How To Achieve More In Life

As I eased my effort and heart rate down to the 150 bpm range, I was able to find a more sustainable groove. Fortunately, my legs felt strong throughout the first 50 miles of climbing and I was glad I drank my Coke early to keep my glycogen stores topped-off. But ultimately my digestion and struggles to eat solid foods lingered for the next 80 miles.

#2 – The really bad moments will eventually get better

It wasn’t long before two strong riders in the front pack caught me. Tristan Smith, an experienced rider who finished second in the race, rode with me for a short while before having to stop due to some seriously cold feet and hands.

He explains his situation well in this podcast, but ultimately the temperatures dropped to freezing as we reached higher elevation and colder pockets of Michigan.

“I am getting in a bad mental place” – Tristan said.

Tristan dropped back out of sight to put on winter gloves and recalibrate his gear. It was only about 15 minutes before he caught back up to me. He was a strong climber and his bike setup appeared fairly minimal with just one partial frame back, a couple of water bottles, and a small hydration pack.

Tristan’s facial hair was glazed over in frost. Despite his frigid appearance, he was pedaling strong and eventually left me behind around mile 60.

As I mentioned above, I too had my own bad moments which peaked between mile 80-120. Eventually forcing myself to eat caused all sorts of stomach discomfort that I mustered through until having to take an unplanned bathroom break at the halfway point. Although it was an unfortunate circumstance that took me out of competition with the two lead riders, I was very happy to be feeling better.

Between my own bad moments and witnessing Tristan’s rebound, it was a firm reminder that not all low points will last. Sure, there are exceptions when the body won’t cooperate. But in most scenarios, the bad moments will get better in time.

The Resilient Athlete

A Self-Coaching Guide to Next Level Performance in Sports & Life

Are you aiming to become a resilient athlete who is able to withstand any pressure? Be able to jump on any opportunity? Take any challenge life throws at you head on?

Then this book is for you.

Learn more#3 – Let the silence do the talking

During some of those bad moments, I kept thinking about Alex Howes and Lachlan Morton’s Dirty Kanza in 2019. In the final quarter of the 200-mile gravel race, Alex said to Lachlan “I’m falling apart, mate.”

And for some reason, I kept attaching that same narrative to my own uncomfortable situation.

I am falling apart.

I literally kept saying that to myself, as if it was going to give me an out or some excuse for not performing my best.

Aware of my negative self-dialogue, I flipped the script on the detrimental chatter. “I may have stomach distress, but my legs are feeling great. I am not falling apart” – I reminded myself.

As a role model mine, Cal Fussman, would always say in the context of being a good listener, “let the silence do the talking.” And at that moment, I needed to listen to myself in silence and not let my mental chatter dictate how I was feeling.

After another desperate bathroom break, my self-narrative changed and became “I am feeling great. I’ve got this.” So, the last 80 miles were strong, fast, and glorious.

The finish line

I finished the race in 15 hours and 3 minutes and was the third rider to cross the finish line – just behind Tristan.

The 2020 Fall edition of the Sancho 200 was a race for the books. It had a 50 percent DNF rate and the finish times were some of the slowest to date. It was a powerful testament to not only a difficult course but the challenging conditions of that day.

As my first ultra adventure bike race, it was an experience that taught me many great lessons. Long-distance adventure events are all about being smart. It dawned on me how simple mistakes early on can evolve into even more problems later down the road.

As simple as it sounds, I realized how important it is to simulate my actual racing experience in training. Most of my training sessions were long-distance, low-intensity rides averaging a 130-140 bpm heart rate. While occasionally I would certainly hit 170+ bpm, I never practiced fueling at that intensity. It was a tough lesson learned that solid foods typically don’t go down easy at such intensities.

Additionally, I learned the importance of minimizing stoppage time. Those two bathroom breaks, combined with predetermined refueling stops, costed me a lot of wasted time. It makes a lot of sense to me now why some of the best adventure cyclists who win big races don’t stop very often or hardly sleep. Minimizing stoppage time is a huge component of being competitive.

Most importantly, Sancho taught me a great deal about mindset and attitude. Positive mental dialogue, present-state awareness, and confidence that bad moments won’t last. These are just a few additional takeaways that will serve me well in my next adventure bike race.

Tyler Tafelsky

Tyler is an avid bikepacker, adventure cyclist, and triathlete based in northern Michigan. When he’s not training or enjoying the great outdoors, Tyler writes for his blogs at Better Triathlete and Yisoo Training.

Tags In

Related Posts

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

GET A FREE TRAINING PLAN

Subscribe to my email list and get access to a free 4-week “back in shape” training plan

You’ll also get two full-body strength sessions and some other goodies!

How did I get here?

Hey there! My name is Andrejs and I am here to inspire, entertain and get you fit for any adventure.

I went from being an over trained pro athlete to an endurance coach sharing how to listen to your body and live life to the fullest.

Traveling, new sports & activities brought new meaning to my training and made it much more effective, fun and enjoyable. And I'm here to help you do the same.