Polarized And 80/20 Training: Everything You Need To Know

Have you ever felt that training makes you more fatigued than fit? Or found yourself catching a cold or picking up an injury too often? Well, it might be that you’re training too hard and have hit a workout plateau. Or have quite an intense life and lack recovery. If it sounds like familiar, you’ll benefit a lot from applying 80/20 training approach or using a polarized training model. Both systems are a great way to bring more structure and balance in both sport and life.

As a coach I frequently get a message that sounds like this – ‘I‘m struggling to get faster. I tried everything – more volume, different intervals, hill repeats, very long runs, strength training – but nothing seems to work. Can you help?’

Unfortunately, this is a situation many amateur and self-coached athletes find themselves in. No, these athletes are not doomed or destined to remain power walkers only. And yes, there is still hope to change things for the better. In this post I’ll share how 80/20 training can help overcome such workout plateau.

But before we jump into the details about polarized and 80/20 training, let’s quickly see what’s the problem?

Moderate intensity – the ‘gray zone’ that stops all the progress

Typically, the most common reason why there are so many frustrated, experiencing burnout or even injured athletes is intensity. In particular – training just a little harder than is required for optimal adaptation.

Yes, a healthy dose of intensity and stress is good for our bodies. Apart from other benefits, high intensity training triggers production of human growth hormone that slows down or even reverses ageing processes.

More stress is not necessarily better if that is not followed by sufficient rest.

There’s a limit to the amount of high intensity training athletes can tolerate. Intense efforts tax our body’s reserves and weaken our immune system. Depending on the fitness level, complete recovery from a hard workout can take anywhere from 1 to 3 days.

We certainly cannot give our best every day. Too much too soon will eventually lead to athlete burnout.

Unfortunately, research suggests that most runners spend more than 50% of their training time at moderate and high intensities. Due to that they fall into the trap of the so-called low return training. They go out for a run or a bike ride and simply push themselves to the point of fatigue without any structure. This is also known as doing junk miles. That makes them feel good about the job done and they do it again and again.

Even though such ‘moderate’ efforts make us feel as if we’re ‘working out’, training like that every day is neither here not there. Not too hard to effectively trigger neuromuscular adaptations and not easy enough to promote recovery or build endurance.

This moderate effort is sometimes referred to as Zone 3 training – that with a target heart rate of 70% to 80%.

What ends up happening as a result of this low return training is that athletes consistently find themselves a little too tired. Always not to their 100% – both physically and mentally. So, when it’s time to go really hard they don’t feel fully fresh. And that affects everything – performance, result, productivity and even confidence.

To be fair, it’s not common sense that each intensity level triggers a different adaptation process and requires a certain ‘recipe’ to be effective. It’s also not fair to say that moderate intensity is ineffective in general. In many cases people aren’t using a structured approach and not even aware they are slowly burning out.

Performance coach can help to spot these signals and adjust the training to ensure the best overall result.

The Resilient Athlete

A Self-Coaching Guide to Next Level Performance in Sports & Life

Are you aiming to become a resilient athlete who is able to withstand any pressure? Be able to jump on any opportunity? Take any challenge life throws at you head on?

Then this book is for you.

Learn moreThe ‘O’ generation and the workout plateau

Actually, It’s not only the above mentioned group of athletes that are left tired and frustrated. How many out there feel the same about work or daily life? Grinding through the week, not recovering enough so that every day feels like a Groundhog Day?

I bet everyone has that friend who’s always overly focused on something. Says he’s tired even after sleeping until 10am. And in general has no energy left for anything in life – only to ‘survive’ until the weekend.

We all are born at different times and our lives and personalities are shaped by different events. But sometimes I think a lot of us, regardless of age, belong to what I call an ‘O generation’. Overworked, Overstressed and Overtired.

Read also: 19 Strategies For Athletes To Reduce Mental Stress & Improve Recovery

The pace of life now is very fast. Being overachievers as we are, we tend to try and squeeze into our lives as much activity as possible. To the extent that we’re in a constant stress and slowly burning out. Not too quickly to get exhausted, but rather slowly – almost unnoticeably. But because it’s ‘comfortably uncomfortable’ we don’t give ourselves permission to slow down and fully recover to get back at it with more force and clear head.

Sounds familiar?

It’s like living in a moderate effort. Always pushing, but not having the energy to push hard enough. Never relaxing and appreciating the moment fully. Waiting for Friday in a state of chronic sleep deprivation, stress and mental & physical fatigue, failing to recover over the weekend. Over time this practice puts an athlete into a chronically fatigued state and doesn’t allow him to give 100% when it actually matters, which leads to workout plateau, overtraining and, inevitably, injuries.

Adding more intensity in such situation in a form of a hard training schedule typically makes things even worse, preventing us from progressing as fast as we could or expect to.

80/20 training – the secret behind peak performance

So how come elite athletes spend their time on training and pushing hard – and still progress?

You might have already guessed where I’m going with this.

The secret behind consistent endurance gains is that most of the training is very easy. So easy, in fact, that when it’s time to go hard athletes have capacity to do so. This approach is called 80/20 training.

In short, it means devoting at least 80% of training time to low intensity. Remaining 20% is then split between moderate & high intensity. This can take various forms. 1 or 2 short and very intense sessions every week mixed with active recovery sessions or a small dose of high intensity during an otherwise easy session.

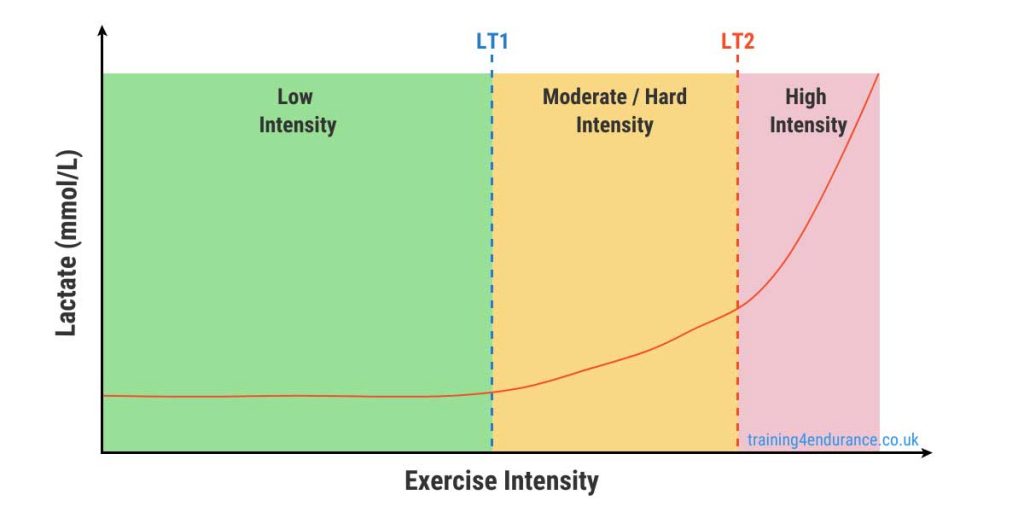

Easy training in this case refers to Zones 1 & 2 (in a 5-zone model) – under first ventilatory threshold (VT1 or LT1). At this intensity an athlete should be able to breathe only through the nose, talk freely and even get the feeling of not exercising at all. But, ironically, this easiness is what develops basic strength & endurance and sets the athlete up for producing maximum performance.

It’s important to not, though, that depending on the phase of the season the share of high intensity will vary. For instance, in the beginning of the season low intensity might take up as much as 95% of the total volume. Whereas closer to the goal race during peak phase it can drop to 70%, leaving more room for race pace practice (i.e. moderate intensity).

Which is why it’s important to consider longer timespan (i.e. a month or two) and follow the 80/20 training rule on a high level.

| Intensity | Zone | Lactate level | Effect |

| Low | Z1 & Z2 | <1.5 mmol/L | Recovery, aerobic base, overall strength |

| Moderate | Z3 | 1.5 – 3 mmol/L | Cardiovascular development |

| High | Z4 & Z5 | >3 mmol/L | Power, speed, resistance to fatigue |

Research about 80/20 training

This type of structure works not only for beginner athletes, but also for established ones. In a study done on sub-elite 5K runners, the group who extended their low intensity training to 80% (compared to the group that focused on moderate training) improved their 10K time by 36 seconds more on average (2:37 min versus 2:01 minutes). That’s a massive margin for an effort that lasts just over half an hour!

There’s even more research and data available in Matt Fitzgerald’s 80/20 running.

This concept of training slow to race fast isn’t new. Legendary coach Arthur Lydiard pioneered this concept back in 1950s with the athletes he worked with. The basic principle behind easy training is that an athlete can increase the overall training volume without adding as much stress as he/she would at moderate & high intensities. This, so called aerobic base, provides athletes with a strong foundation to execute even more high intensity training that they could have.

What is polarized training?

Polarized training takes this one step further. It avoids the moderate intensity (Zone 3 + low-Zone 4) altogether. The purpose of it is to put a larger focus on the quality of the high intensity training by making easy days really easy and hard days really hard.

Most of the high intensity training in polarized training model should be done primarily in Zones 4 & 5. This is hard. When done right, such kind of training really hurts, feels unsustainable and some athletes might think they are doing more harm than good. Which is why many often slide to a more manageable moderate effort.

However, with a well planned combination of intervals and rest this approach stimulates more significant speed adaptations and produces great results. Coaches agree that polarized training model provides more fitness benefit at lower ‘price’ (less global stress induced). So, athletes are physically and mentally fresher for their quality sessions and are less likely to suffer from burnout, over-training or injuries.

Many long distance athletes at some point of time feel that their muscles get ‘lazy’. They are comfortable with low and moderate effort, but seemingly lose the ability to produce high power. As a result, their paces during shorter duration races lie in a very narrow range. For example, they are able to run a similar pace for 1K that they do for a 5K.

Mostly, this is linked to higher volumes and little variety in paces. Muscles work in a similar contraction range and gradually the body loses the ability to recruit more muscle fibers and produce more powerful output. This not only leads to workout plateaus, but might also increase injury risk as it promotes the overuse of the same limited pool of muscle fibers.

Read also: 12 Effective Strength Building Workouts For Any Experience Level

Polarized training in everyday life

There are some parallels between sport and everyday life here as well.

It might sound like a paradox, but often slowing down can help us go faster in life. Things like getting enough quality sleep or meditating are great ways to minimize mental stress, which, in turn, makes us more productive. Or reducing the amount of commitments we have helps us focus on one thing much deeper.

As an experiment, try to apply polarized training model to other areas of life.

Don’t multitask. Drop or put on hold some of the action points or projects you are working on. Instead, select one or two most impactful initiatives and put your heart and soul into doing those.

And when it comes to rest – rest completely. Go out to the nature, spend time with friends, do a digital detox, be present and mindful of every moment.

6 Steps to an effective 80/20 training model

In short, polarized training means training most of the time very easy. And then – when the body is at full capacity – train really really hard.

As usual, it’s a bit more complicated than that, so below are some of the tricks that can help athletes make polarized training work for them and break through the workout plateau.

#1 Train in zones

First things first. If you’re not doing it yet, train in zones.

The quality of the output is the quality of inputs. If an athlete wants to improve performance, he/she has to put in quality sessions that trigger specific physiological processes and adaptations in the body.

Each training zone corresponds to a certain intensity level. Planning and using them in training is the best way to control the adaptations that are triggered during the session and add structure to the whole training process.

It’s also a great way to learn more about your body and understand how every intensity feels. This comes in very handy when pacing a race.

Read also: 5 Heart Rate Training Zones – A Guide To Maximum Endurance Gains

#2 Increase overall volume

One of the factors that consistently predict high performance is the amount of workload an athlete does. Which is true for any area of life, actually.

The more we do something, the better we become at it.

For amateur athletes one of the most efficient ways to significantly improve fitness and results is to increase the overall training time.

The Resilient Athlete

A Self-Coaching Guide to Next Level Performance in Sports & Life

Are you aiming to become a resilient athlete who is able to withstand any pressure? Be able to jump on any opportunity? Take any challenge life throws at you head on?

Then this book is for you.

Learn moreLuckily, 80/20 training provides a good framework for that, as it ensures most of the volume is at low intensity. This, in turn, develops a solid aerobic base and prevents burnout that could be caused by more intense sessions.

Athletes who are new to low intensity training might have hard time overcoming the idea that they are not pushing themselves enough. However, volume will do its magic and it’s the consistency that builds overall strength, endurance and resilience across the body.

#3 Break up the time at lactate threshold

Besides moderate intensity efforts there is one other type of training that is similarly taxing on the body. That is lactate threshold training.

Efforts done at lactate threshold provide much more fitness benefit than those at moderate intensity. However, the way they are usually done (20-30 minute tempo efforts) requires a lot of recovery afterwards.

Instead, a more effective way to improve lactate threshold is to cut the total effort into smaller chunks and add short breaks in between. For lactate threshold to improve the most important factor is the total time at threshold effort. So, by allowing the body to recover a little it’s possible to increase the amount of intervals and therefore the total time at threshold.

So, instead of 20 minutes at threshold a much more effective session would be to do 5×5 minute threshold intervals and include, say, 1-2 minute Zone 2 aerobic efforts in between. That’s even more time at threshold!

#4 Add VO2max training

Now on to the real value of the polarized training model – VO2max sessions. These are called so because they focus on maximum oxygen capacity efforts and are specifically designed to get athletes uncomfortable in a short amount of time.

VO2max intervals are typically short (up to 2min) and rest between each interval is even shorter (often 50% of the interval). The intensity of the session is very high and helps to develop power, improve efficiency and improve body’s resistance to fatigue.

These sessions are very uncomfortable and cause, among other things, shortness of breath and acute muscle stiffness. Such training is only effective when the body is fully recovered. Since many athletes are in a state of chronic fatigue, they dread or stay away from these very hard sessions.

Read also: How To Measure Post Workout Recovery And Avoid Accumulated Fatigue

#5 Include sprints, plyometrics and explosive strength training into your 80 20 running plan

The simplest way to incorporate polarized training into your schedule is to add some explosive movements after your easy workout.

This might be a series of strides (fast speed pickups) included at the end of an easy session. It doesn’t have to cost any more time than the session itself, but your body will thank you for it in the long term.

Another option is to do a couple of rounds of jumping exercises (plyometrics) or heavy lifting at least once a week. Again, this doesn’t have to be long – 5-10minutes would be more than enough.

#6 Don’t forget about easy days and recovery weeks

Over-reaching and over-training is very hard to spot in the very beginning. There is this euphoria of having a lot of energy and excitement to push yourself on every training. Unfortunately, this excitement can prevent an athlete from spotting the first signs of fatigue.

The key to proportionally increasing the intensity and workload is to include recovery days and weeks where the intensity and volume is lower.

Such practice allows the body to rebuild torn tissues, ‘calm down’ the nervous system and become stronger. This adaptation is called supercompensation and needs to happen on a regular basis to ensure sustainable progress and results.

You know that feeling when after an easy day or two you feel that the same effort feels easier? That’s supercompensation in action.

Get in the habit of having an easy session/day following a hard one.

During those recovery sessions the aim is not to rack up miles or hit the numbers (those will be way off anyway). Those sessions are there to just move the blood around the body, open up joints and speed up recovery.

Similarly, a good practice is to add a recovery week every 3-4 weeks where focus is more on Zone 1 & 2 aerobic effort. A full week will have an effect not only on the muscles, but also will help to calm down the nervous system which takes much longer to recover.

Struggling with including recovery sessions? Take them first thing in the morning.

Did you find this information useful? Share the post with others using the buttons below.

Have an opinion? Share via links below and tag @theathleteblog

Tags In

Andrejs Birjukovs

GET A FREE TRAINING PLAN

Subscribe to my email list and get access to a free 4-week “back in shape” training plan

You’ll also get two full-body strength sessions and some other goodies!

How did I get here?

Hey there! My name is Andrejs and I am here to inspire, entertain and get you fit for any adventure.

I went from being an over trained pro athlete to an endurance coach sharing how to listen to your body and live life to the fullest.

Traveling, new sports & activities brought new meaning to my training and made it much more effective, fun and enjoyable. And I'm here to help you do the same.